Welcome to our CEO, Tom Reeves, as he shares the last of his 4 blogs with ideas to consider. Add your reactions to the post below and use the the contact button above so we can continue the discussion!

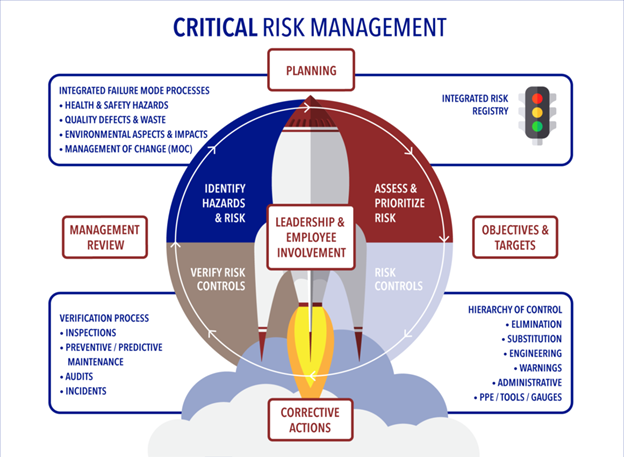

Early in my career, I worked as a junior safety professional in a large manufacturing plant. This plant had over 1600 workers and these workers made large home appliances. One of the worker jobs on the production line was especially troubling. It was ergonomically difficult and after about three months, the typical worker would often be injured to the point of needing surgery. The company tried for years to fix the ergonomic issues associated with this job. The latest solution had been to add a helper to the job who would stage parts to reduce the ergonomic risk to the operator. That solution resulted in delaying the injury but, sadly, did not prevent it.

The risk with the job was two-fold. Both risks involved installing a rubber boot-shaped part that served as part of the water drainage system into the bottom of the appliance. First, the worker would put their hand through the boot in an awkward down-facing position. Then, the worker would seat the boot into a slot at the bottom off the appliance by extending their arm. The worker would then use both thumbs to press the edges of the rubber boot into a hard plastic ring at the bottom of the appliance. It took a few weeks for the worker to develop thumb and wrist pain. If the worker remained in the job for three months, they often needed resulted surgery to repair either the thumbs, wrists or both. Something had to change.

The plant leadership and our corporate level EHS support was very focused on reducing and eliminating the injuries at this workstation. As a newly minted safety professional who wanted to prove himself, I was also very determined to fix this job – perhaps too eager. Luckily, my boss introduced me to a toolmaker in the maintenance department and we began discussing approaches to creating a tool to get the worker’s hand out of the rubber boot. We both visited the workers doing the job on different shifts and asked for their input. The workers were enthusiastic to give their ideas. We drew up a prototype concept and the tool maker built it. The prototype involved a wooden block the size of the top oval ring of the boot. The edges of the wooden block were rounded allowing the block to rock back and forth. Then, we mounted an angled handle to the top. If the prototype worked, we’d eventually fabricate a version made of more durable materials and mount it to a zero-gravity connection to further remove stress. But, first, the prototype needed to be tested.

The rubber boot had critical to quality requirements. If the boot was not seated and secured properly, the appliance would leak water into someone’s nice kitchen. Every appliance was leak tested at the end of the assembly line and a small percentage of the appliances consistently failed the leak test and required rework. Our initial hope was that using this tool would result in a net-zero change in the results of the leak tests while reducing the ergonomic strain and risk of the job. After a few initial tests with the prototype and after making a few tweaks to the design, we settled on a third version that seemed to work very well.

Using the new tool, the job changed. The worker still had to use their hand to seat the boot in place but now the worker needed to be less exact with their placement. This resulted in less pronation of the wrist and far less force on the fingertips and thumb. The tool did most of the work to secure the boot into the oval hard plastic ring. The new method involved rocking the tool back and forth in with the wrist and hand in an ergonomically neutral position — it was determined three times was optimal for seating the boot ring. The tool made the job easier, faster, reduced ergonomic strain, and much to our surprise, it greatly improved the performance on the leak tests.

At the time, I could not imagine a bigger success. Workers, supervisors, a toolmaker, and a young safety professional had worked together to discover a viable solution to a job that reduced risk, made the job more efficient, and improved product quality. That is when the project crashed in ways we did not anticipate.

Once the worker began to use the tool, the task was completed faster. This triggered the industrial engineers to do a time-study. A time-study is where a job is assessed for the time the worker is utilized. If a job utilized the worker more than 80%, a helper was used. Prior to instituting the tool, the worker was utilized close to 90% of the time, so that was the reason for the helper. But, using the tool, the worker’s time was reduced to about 50% utilization. According to the work rules, the helper was no longer needed. In this case, the helper’s job was eliminated. That is when I received my first grievance. The representatives argued the tool was a significant change to the job and should not be allowed. Then, the tubs began to fail the leak tests at a greater rate – the tool was blamed, and the workers claimed the helper was still needed. That is when the operations manager and plant manager called me and my boss to their office and asked why I was causing trouble. I was baffled. I thought we made the jobs safer, increased quality, and efficiency. I had no idea I had hit a cultural landmine.

The tool was immediately abandoned, and the workers went back to the old way of doing the job. While working on this project, I had been recruited by a different company to take another role and decided to accept the job. Within a few weeks I was gone — but I was still shocked by what happened. After a few weeks in my new job, a package showed up with a note. It was from my old boss. The package contained two things: the prototype, which he painted gold, and a note that simply said, “You did the right thing.”

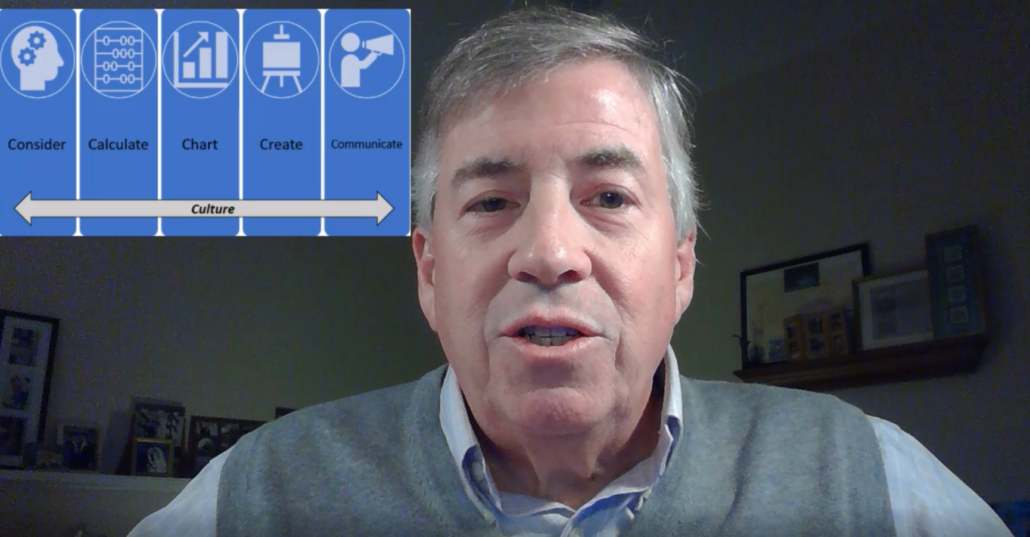

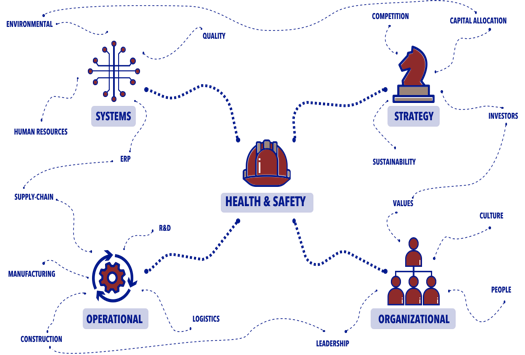

I do not believe I could have learned two greater lessons at this early point in my safety professional career. The first lesson was to be mindful of my eagerness to prove myself. The second lesson, to paraphrase the great management consultant, Peter Drucker, is that culture eats everything for breakfast [Hyken: 2015] and while the tool maker and I had developed a technological solution for a problem, I failed to recognize and navigate all of the organizational factors this change would trigger due to a combination of my eagerness and my lack of understanding. The lesson is that there are organizational forces, which, if not addressed, can greatly resist change — even when the change is good. To this day, that gold-painted prototype sits on my desk as a reminder to think and act holistically in any change.